Whether you like them or not, cookies are an essential part of modern web development. Yet, they are often misunderstood amongst developers and sometimes used where they shouldn’t have been or are missing attributes that can make your website vulnerable. This article will discuss how browser cookies work, how you can access and manipulate them both from the client and server, and how to control their visibility in the browser using their attributes and make your cookies more secure. We'll also take a brief look at privacy concerns related to third-party cookies at the end.

What are cookies, and how do they work?

A browser cookie is a small piece of data stored in the browser that can be created either by the client-side JavaScript or by the server during an HTTP request. The browser can then send that cookie back with later requests to the same server and/or let the client-side JavaScript of the webpage access cookie when the user revisits the page.

Cookies are generally used for session management, personalization (themes or similar settings), and tracking user behavior across websites.

There was a time when cookies were used for all kinds of client-side storage. But there's was an issue with this approach; since all the cookies for a domain are sent with every request to the server on that domain, they could significantly affect performance, especially with low bandwidth mobile data connections. For the same reason, browsers also typically set limits for the size of the cookie and the number of cookies allowed for a particular domain (Typically 4kb and 20 per domain).

With the modern web, we got the Web Storage APIs (localStorage and sessionStorage) for client-side storage, which allow browsers to store client-side data in the form of key-value pairs. So if you want to persist data only on the client-side, then using these APIs would be a much better way to do it because they are much more intuitive and easy to use than cookies and can store much more data (usually up to 5MB).

Setting and accessing cookies

You can set and access the cookies both via the server and the client. Cookies also have various attributes that decide where and how they can be accessed and modified, which we will discuss in detail in the next section. First, let's look at how you access and manipulate the cookies on the client and the server.

Client (Browser)

The JavaScript that is downloaded and is executed on the browser whenever you visit a website is generally called the client-side JavaScript. It can access the cookies via the Document property cookie, i.e., you can read all the cookies that are accessible on the current location with document.cookie. It gives you a string containing a semicolon-separated list of cookies in key=value format.

const allCookies = document.cookie;

// The value of allCookies would be something like

// "cookie1=value1; cookie2=value2"Similarly, to set a cookie, we need to set the value of document.cookie setting the cookie is also done with a string in key=value format with the attributes separated by a semicolon.

document.cookie = "hello=world; domain=example.com; Secure";

// Sets a cookie with key as hello and value as world, with

// two attributes SameSite and Secure (We will be discussing these

// attributes in the next section)Just so you're not confused, the above statement does not override any existing cookies; it just creates a new one or updates the value of an existing one if a cookie with the same name already exists.

Now I know this is not the cleanest API you have ever seen. That's why I would recommend using a wrapper or a library like js-cookie to handle client cookies.

Cookies.set('hello', 'world', { domain: 'example.com', secure: true });

Cookies.get('hello'); // -> worldNot only does it provide a clean API for CRUD operations on cookies, but it also supports TypeScript, thus helping you avoid any spelling mistakes with the attributes.

Server (Node.js)

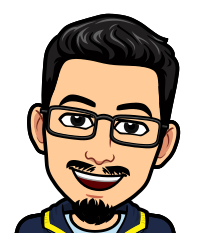

The server can access and modify cookies via an HTTP request's request and response headers respectively. Whenever the browser sends an HTTP request to the server, it attaches all the relevant cookies to that site with the cookie header. Check the request headers of probably any web app you use, and you'll find the cookies being sent to the server with request headers as a semicolon-separated string.

You can then read these cookies on the server from the request headers. For example, if you are using Node.js on the server, you can read them from the request object like the snippet below, and you will get the semicolon-separated key=value pairs similar to what we saw in the previous section.

http.createServer(function (request, response) {

var cookies = request.headers.cookie;

// "cookie1=value1; cookie2=value2"

...

}).listen(8124);Similarly, to set a cookie, you can add a Set-Cookie header in the response headers, with cookie in the key=value format and attributes separated by semicolon, if any. This is how you can do it in Node.js -

response.writeHead(200, {

'Set-Cookie': 'mycookie=test; domain=example.com; Secure'

});Also, chances are you won't be using plain Node.js; instead, you would be using it with a web framework like Express. Accessing and modifying cookies gets much easier with Express. For reading, add a middleware like cookie-parser, and you get all the cookies in form of an JavaScript object with req.cookies. You can also use the built-in res.cookie() method that comes with Express for setting cookies.

var express = require('express')

var cookieParser = require('cookie-parser')

var app = express()

app.use(cookieParser())

app.get('/', function (req, res) {

console.log('Cookies: ', req.cookies)

// Cookies: { cookie1: 'value1', cookie2: 'value2' }

res.cookie('name', 'tobi', { domain: 'example.com', secure: true })

})

app.listen(8080)And yes, all this is supported with TypeScript, so there is no chance of typos on the server as well.

Attributes of cookies

Now that you know how you can set and access cookies let's dive into the attributes of cookies. Apart from name and value cookies also have attributes that control a variety of aspects which include the security aspects, lifetime and where and how they would be accessible in the browser.

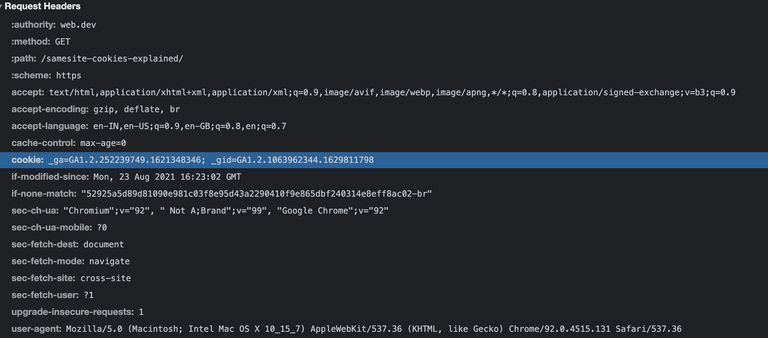

Domain

According to MDN, the domain attribute tells the browser which hosts are allowed to access a cookie. If unspecified, it defaults to the same host that set the cookie. So when accessing a cookie using client-side JavaScript, only the cookies that have the domain same as the one in the URL bar are accessible. Similarly, only the cookies that share the same domain as the HTTP request's domain are sent along with the request headers to the server.

Remember that having this attribute doesn't mean that you can set cookies for any domain because that would obviously be a huge security risk. (Imagine an attacker on evil.com creating the cookies for your site awesome.com.)

So the only reason this attribute exists is to make the domain less restrictive and to make the cookie accessible on subdomains. For example, if your current domain is abc.xyz.com, and when setting a cookie if you don't specify the domain attribute, it would default to abc.xyz.com, and the cookies would be restricted only to that domain. But, you might want the same cookie to be available on other subdomains as well, so you can set Domain=xyz.com to make it available on other subdomains like def.xyz.com and the primary domain xyz.com.

Also, this does not mean that you can set any domain value for cookies; TLDs like .com and pseudo TLDs like .co.uk would be ignored by a well-secured browser. Initially, browser vendors maintained lists of such public domains internally, which inevitably caused inconsistent behavior across browsers.

To tackle this, the Mozilla Foundation started a project called the Public Suffix List that records all these public domains and shares them across vendors. This list also includes services like github.io and vercel.app that restricts anyone from setting cookies for these domains, making abc.vercel.app and def.vercel.app count as separate sites with their own separate set of cookies.

Path

This attribute specifies the path in the request URL that must be present to access the cookie. Apart from restricting cookies to domains, you can also restrict them via path. A cookie with the path attribute as Path=/store would only be accessible on the path /store and its subpaths /store/cart, /store/gadgets, etc.

Expires

This attribute allows setting an expiration date after which the cookies are destroyed. This can come in handy when you are using a cookie to check if the user has been shown an interstitial ad, and you can set the cookie to expire in a month so that the ad can be shown again after a month.

And guess what? It is also used to remove cookies by setting the Expires date in the past.

Secure

A cookie with the Secure attribute is only sent to the server over the secure HTTPS protocol and never over the HTTP protocol (except on localhost). This helps in preventing Man in the Middle attacks by making the cookie inaccessible over unsecured connections. Unless you are serving your websites via an unsecured HTTP connection (which you shouldn't) you should always use this attribute with all your cookies.

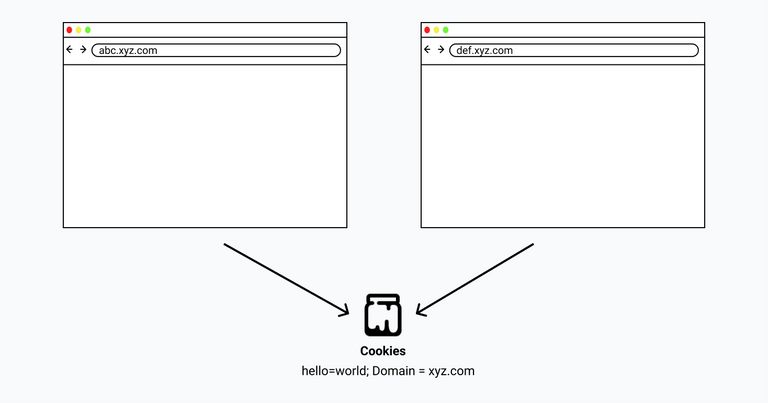

HTTPOnly

This attribute, as the name probably suggests, allows cookies to be only accessible via the server. So, only the server can set them via the response headers, the browser will then send them to the server with every subsequent request’s headers, and they won’t be accessible via the client-side JavaScript.

This can partially help secure cookies with sensitive information, like auth tokens, from XSS attacks since any client-side script won't be able to read the cookies. But remember it does not guarantee complete security from XSS attacks. Its because, if the attacker can execute third-party scripts on your website, then they might not be able to access the cookies, but instead, they can directly execute any relevant API requests to your server and the browser will readily attach your secure HTTPOnly cookies with the request headers. So imagine one of your users visits a page where the hacker has injected their malicious script on your website. They can execute any API with that script and act on the user's behalf without them ever knowing.

The point is when people say that HTTPOnly cookies cause XSS attacks to be useless, they are not completely correct because if a hacker can execute scripts on your website, you have much bigger problems to deal with. There are ways to prevent XSS attacks, but they are out of the scope of this article.

SameSite

If you remember, at the beginning of this article, we saw how cookies for a particular domain are sent with every request to the server for the corresponding domain. This means that if your user visits a third-party site and if that site makes a request to APIs on your domain, then all the cookies for your domain will be sent along that request to your server. This can be both a boon and a curse depending on your use case.

Boon in case of something like YouTube embeds. So, for example, if a user who is logged in to YouTube on their browser visits a third-party website containing YouTube embeds, they can click on the "Watch Later" button on the embed and add it to their library without needing to leave that website. This works because the browser sends the relevant cookies for youtube.com to the server confirming the user’s authentication status. These types of cookies are also called third-party cookies.

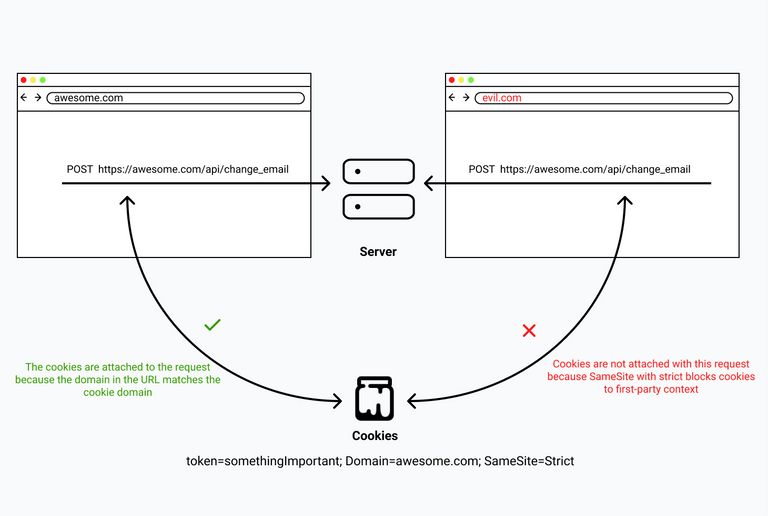

A curse in basically any other case you didn't intend it to happen. Imagine a case where the user visits a malicious website where that website makes a request to your server, and if your server doesn't validate the request properly, then the attacker can take actions on the user's behalf without their knowledge. This is basically what we call a CSRF attack.

To help prevent this type of attack, the IETF in 2016 proposed a new attribute in cookies called SameSite. This attribute helps to tackle the above problem by allowing you to restrict your cookies only to the first-party context, i.e., only attach cookies to the request when the domain in your URL bar matches the cookie's domain.

There are three types of values you can set for the SameSite attribute:

Strict: When set to strict, your cookies will only be sent in a first-party context.Lax: This value is slightly less restrictive thanStrictby allowing the cookies to be sent with Top-Level navigations. This means the cookie will be sent to the server with the request for the page in cases like when a user clicks on your website from a google search result or is redirected via a shortened URL.None: As the name suggests, this attribute allows you to create third-party cookies by sending the relevant cookies with every request irrespective of the site user for the cases like that of YouTube embeds we discussed above.

You can learn more about the SameSite attribute in detail with this awesome article by web.dev.

Privacy and third-party cookies

We saw a brief explanation of what third-party cookies are in the previous section. In short, any cookie set by a site other than the one you are currently on is a third-party cookie.

You may also have heard about how infamous third-party cookies are for tracking you across websites and showing personalized ads. Now that you know the rules of cookies, you can probably guess how they might do it.

Basically, whenever a website uses a script or adds an embed via iframe for third-party services, that third-party service can set a cookie for that service's domain with HTTP response headers. Also, these cookies can be used to track you across websites that use the same third-party service's embeds. And finally, the data collected by these third-party services by identifying you via the cookies can then be used to show you personalized ads.

To tackle this, many browsers like Firefox have started blocking popular third-party tracking cookies via a new feature they call ETP (Enhanced tracking protection). Although this protects users from the 3000 most common identified trackers, its protection relies on the complete and up-to-date list.

Hence browsers are eventually planning to get rid of third-party cookies. Firefox is implementing state partitioning, which will result in every third-party cookie having a separate container for every website. You can read about how it works in more detail on their blog.

Now you might think that something like State Partitioning will also break legitimate use cases for third-party cookies apart from tracking, and you're right. So browsers are working on a new API called Storage Access, which will allow third-party context to request first-party storage access via asking permission from the user, which would give the service unpartitioned access to its first-party state. Again if you're more interested in how it works in detail, you can check it out on the same blog by Mozilla.

Conclusion

I hope this article helped you learn something new about JavaScript cookies and gave you a brief overview of how they work, how they can be accessed and modified from the server and the client, and lastly, how the different attributes of cookies let you control their visibility and lifespan in the browser.