Classes in JavaScript are a blueprint for creating objects which allow you to encapsulate, data with code to work on that data. The class keyword was officially introduced in JavaScript with ES6 in 2015, but the classes created with the class keyword are mostly just syntactic sugar over the already existing pre-ES6 syntax for creating objects with custom prototypes.

So in this article, we'll explore what prototypes are, what are they used for, what prototype chaining is and how it helps with prototypal inheritance, and then finally, how do classes work under the hood with all these concepts. Throughout this article we'll also be looking at examples which you can try out yourself with any JavaScript compiler or even the browser console.

What are prototypes anyways?

Prototypes are a core part of JavaScript, so much so that JavaScript is often referred to as a prototype-based language.

Although it is entirely possible that you've been using JavaScript for a while now and haven't ever heard about prototypes (they're mostly abstracted out by the syntax) and knowing about them might not directly help in the day-to-day code we write but it will help you get a better understanding of JavaScript.

In a nutshell, prototypes are a mechanism by which JavaScript objects can inherit features from one another. Objects can have a prototype object which they use as a template to inherit their properties and methods from.

Have you ever wondered whenever you create an object or an array you get a bunch of handy methods ( hasOwnProperty , toString, etc.) out of the box even though you didn't define them when you created the object or the array?

let obj = { name: "Prateek" };

obj.hasOwnProperty("name"); // true

let nums = [1, 2, 3];

nums = nums.map(num => num + 1); // [2, 3, 4]Whenever you create objects and arrays in JavaScript, they come with their default prototype and the properties you saw above, defined on the default prototypes of Object and Array, respectively.

The way it works is that whenever you try to access a property on an object like obj.hasOwnProperty above, JavaScript first checks whether the object has a property called hasOwnProperty or not. If the property isn't defined on the object, it looks into its prototype, and if it cannot find it there, only then it returns undefined. In the example above, hasOwnProperty is a function defined on the Object's prototype; hence we are able to call it.

You can see all the methods like hasOwnProperty, that are available with the default Object prototype under [[Prototype]], just by logging any object in the console.

![The prototype visible under [[Prototype]] in console](/img/prototypes-in-console-768.jpeg)

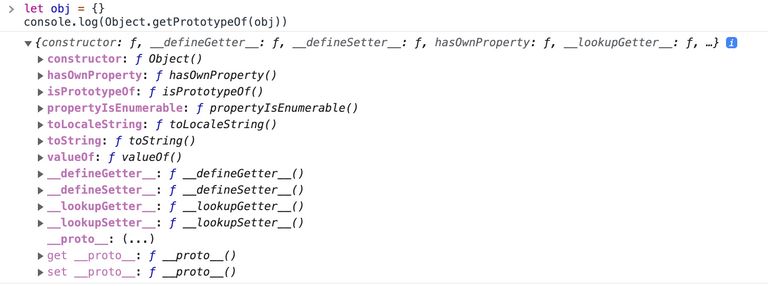

To get the prototype of any object, you can use the Object.getPrototypeof method. Try running the below snippet in the console:

let obj = { foo: 'bar'}

console.log(Object.getPrototypeOf(obj))

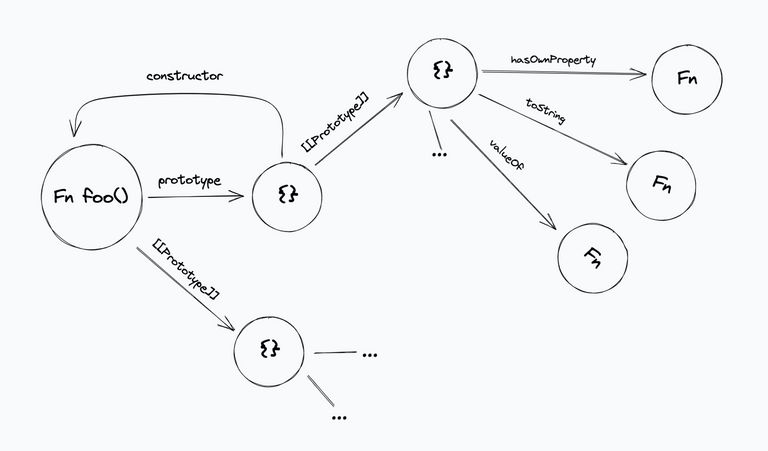

Here is a visualization to help you understand how it works:

You might think that since the prototype is just a JavaScript object, what happens if you mutate it. Try running the below snippet in the browser console and see what happens.

let obj = { name: 'jon' }

let prototype = Object.getPrototypeOf(obj)

prototype.foo = 'bar'

console.log(obj.foo)

let obj2 = { name: 'arya' }

console.log(obj2.foo) // "bar"Since we mutated the default Object prototype which is referenced by all the objects by default, accessing the foo property on any of them would give you "bar" as the value.

What we just did above is known as prototype pollution, it used to be a popular way to add custom properties to shared objects, but it was not only dangerous (imagine an attacker making application-wide changes by modifying the prototype), with modern browsers it is also a very slow operation hence it's not recommended.

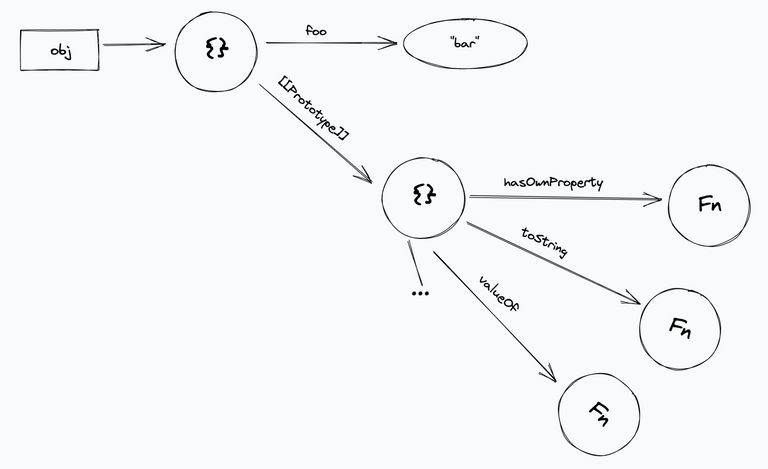

The recommended way to create objects with a custom prototype is using Object.create with accepts the prototype as its argument.

let car = {

wheels: 4,

honk: function() {

console.log('Beep!')

}

}

let prius = Object.create(car)

prius.manufacturer = 'Toyota'

console.log(prius.manufacturer) // 'Toyota'

console.log(prius.wheels) // 4

console.log(prius.honk()) // Beep!Again, here's a visualization to help you better understand the above snippet:

In the above example, the object prius has car as its prototype, so it would be able to access the properties of the prototype while adding some of its own properties as well. With this example I think you might be starting to understand how prototypes can be used for inheritance in JavaScript. We'll be exploring this in more detail and revisiting this method in ther next sections.

The prototype for creating prototypes

In the last section, we saw the role of prototypes in JavaScript objects, how you can manipulate object prototypes and how you can create an object with a custom prototype via Object.create. Although creating objects with custom prototypes via Object.create is not ideal because you cannot set any properties on the object while creating the object, also the syntax is not very neat.

So, now let's take a look at another more prevalent way of creating objects with custom prototypes that you may have seen/used before, constructor functions.

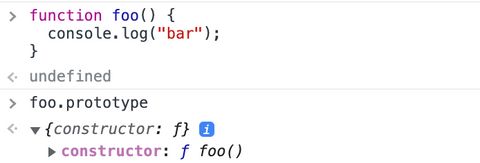

Before we dive into what constrctor functions are and how they work, let's look at an interesting thing about JavaScript functions. Whenever you create a function in JavaScript, it has a prototype property which is an object and that object has a property called constructor that points back to the function itself. You can go ahead and try creating a function and logging the prototype property in the browser to see it for yourself. We'll be looking at why it exists in a minute.

Hence if you do foo.prototype.constructor === foo it would return true

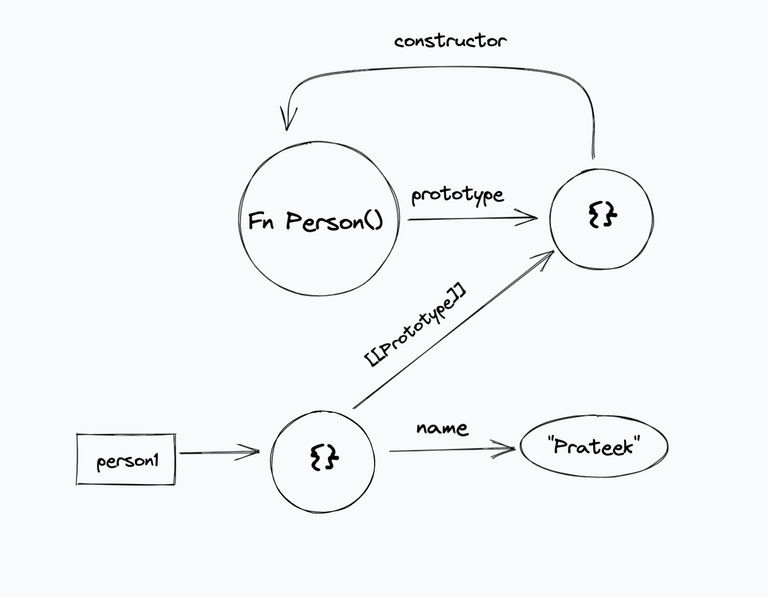

Now that we know about the prototype property of functions let’s take a look at how it helps with creating objects with custom prototype via constructor functions:

function Person(name) {

this.name = name;

}

let person1 = new Person("Prateek")

console.log(person1.name) // Prateek

console.log(Object.getPrototypeOf(person1)) // { constructor: function Person }In the above snippet, we have a regular function with a property name defined on its execution context, via the this keyword. When we invoke a function with the new keyword, apart from executing the function it does a bunch of other things:

- To begin with, it creates a new blank JavaScript object and sets the prototype of that object to the

Personfunction’sprototypeproperty. - Next, it points this newly created object to the

thiscontext of the function (i.e., all references tothisinside the function now point to the newly created object, so in our case, the name property gets defined on that object). - Lastly, if no object is being returned from the function, it returns

this.

Now I guess you might have understood how we got the output in the logs for the above snippet.

Since the name property is defined on this, we get an object with the name property whose value is the argument that we to the function. Also, the newly created object's prototype points to our function's prototype property.

You can further verify it by running the following code:

console.log(Object.getPrototypeOf(person1) === Person.prototype) // trueYou can now also create properties on the function's prototype property and since it is the prototype shared with all the objects created with Person as the constructor function, it would also be available to all those objects.

Person.prototype.sayHello = function() {

console.log(`Hello, ${this.name}`)

}

person1.sayHello() // Hello, PrateekPrototype chaining

Until now, we saw how prototypes in JavaScript work and how JavaScript searches for the property in the prototype if it cannot find that property in that object.

Now you might wonder what if the prototype had another prototype, and that prototype had another prototype, and so on... Will JavaScript keep looking for the property down that chain?

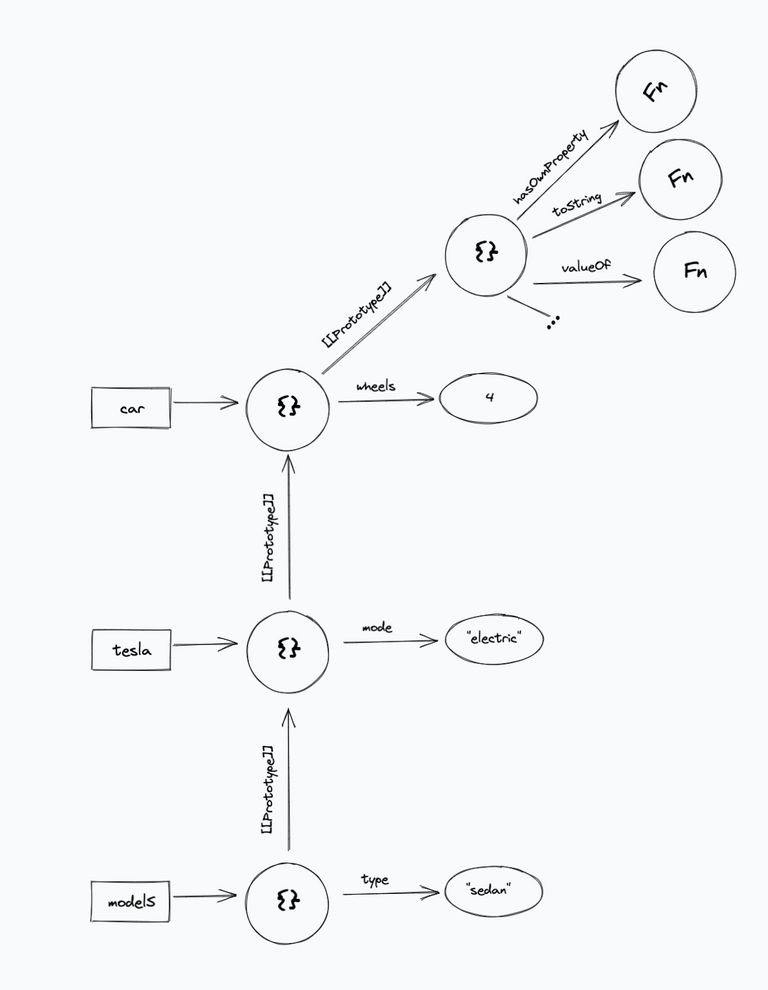

Well the answer is yes. Try running the below snippet in console to see how it works:

let car = {

wheels: 4

}

let tesla = Object.create(car)

tesla.mode = 'electric'

let modelS = Object.create(tesla)

modelS.type = 'sedan'

console.log(modelS.wheels) // 4

console.log(modelS.mode) // electricSo whenever you access a property on an object, JavaScript looks if that property exists on that object. If not, it looks for it in its prototype and keeps repeating the same behavior until it reaches the end of the prototype chain and returns undefined only if nothing is found at the end of the chain.

Now that we have an idea of how prototype chaining works let's see how we can use it to implement inheritance with constructor functions.

Consider we have the following constructor function:

function Human(name, age, gender) {

this.name = name

this.age = age

this.gender = gender

}

Human.prototype.introduce = function () {

console.log(`Hey there! I'm ${this.name}`)

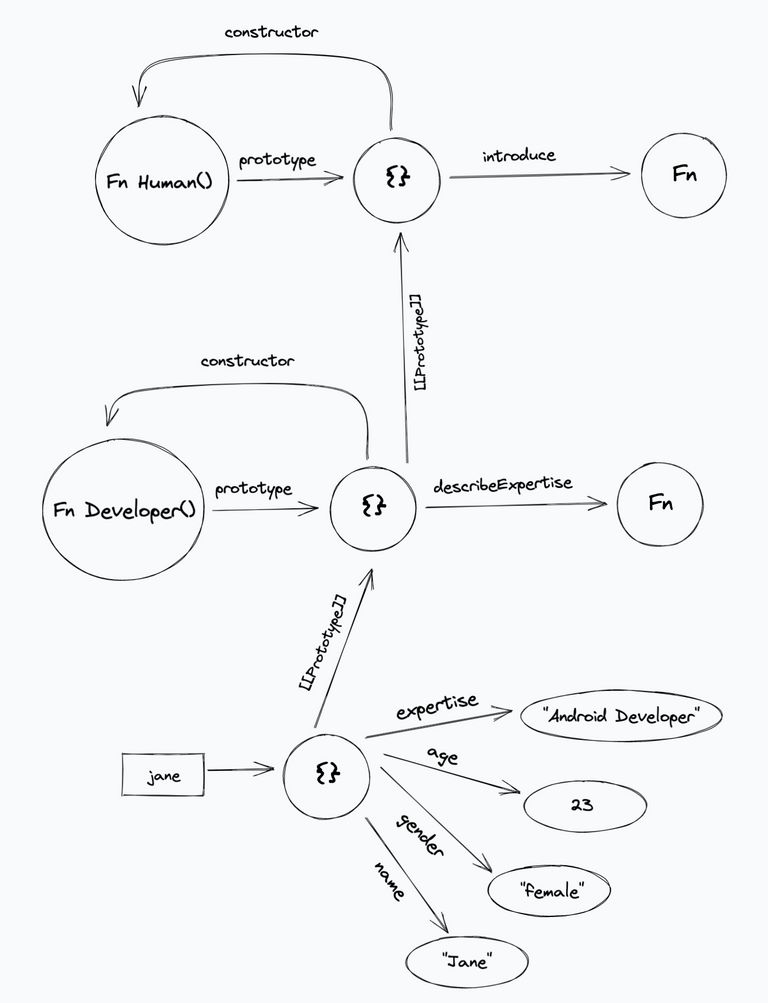

}Let’s assume we want to create another constructor function called Developer that inherits from the above function.

function Developer(name, age, gender, expertise) {

Human.call(this, name, age, gender)

this.expertise = expertise

}In the above snippet, we use JavaScript’s call method to bind the Developer function’s this context when calling the Human function. The call method accepts the this context as the first argument and passes the rest of the arguments to the function itself.

But just calling the constructor function isn't enough since you won't be able to access the prototype methods and variables. The Developer function's prototype property is still the default one which is just an object with the constructor property that references the function itself.

let john = new Developer("John", 23, "male", "Frontend")

console.log(john.age) // 23

console.log(john.expertise) // Frontend

john.introduce() // TypeError: john.introduce is not a functionSo to fix that, we'll be using our old friend Object.create to create a new object Human.prototype as its prototype, and set Developer.prototype to that value:

Developer.prototype = Object.create(Human.prototype)Although this introduces a minor issue that the Developer function's constructor property now points to the Human function because we overrode its prototype, it is not something that we would want.

console.log(Developer.prototype.constructor === Human) // trueTo fix that we'll define the constructor property on Developer.prototype that points to the function again

Developer.prototype.constructor = DeveloperYou can now also define new properties on Developer.prototype and access them on the objects created via the Developer constructor function

Developer.prototype.describeExpertise = function() {

console.log(`Hello I'm ${this.name} and I'm a ${this.expertise}`)

}Let's try creating a new object, with the Developer constructor function

const jane = new Developer("Jane", 23, "female", "Android Developer")

jane.introduce() // Hey there! I'm Jane

jane.describeExpertise() // Hello I'm Jane and I'm a Android DeveloperAgain here’s a visualization to help you grasp what’s happening here:

Classes in JavaScript

So now that we understand how prototype and prototype chaining work and how they allow for prototypal inheritance in JavaScript, let's look at how these concepts apply to JavaScript classes.

As I mentioned in the beginning of the article, the class keyword was officially added to JavaScript with ES6 in 2015. The classes created with the class keyword are primarily syntactic sugar over the prototypal inheritance we saw in the previous section. Still, they also have some syntax and semantics that are not shared with pre-ES6 class-like semantics.

For example, let's take the Human function that we created in the previous section, adding it here for reference:

function Human(name, age, gender) {

this.name = name

this.age = age

this.gender = gender

}

Human.prototype.introduce = function () {

console.log(`Hey there! I'm ${this.name}`)

}The equivalent class code for the above function would be

class Human {

constructor(name, age, gender) {

this.name = name

this.age = age

this. gender = gender

}

introduce() {

console.log(`Hey there! I'm ${this.name}`)

}

}As you can see, the syntax with class is much easier to understand and is similar to what you might have seen in some other languages. It gets even better when it comes to inheritance. Remember the changes we had to make to the Developer function so that it could inherit the prototype from Human. Let's retake a look at it for reference:

function Developer(name, age, gender, expertise) {

Human.call(this, name, age, gender)

this.expertise = expertise

}

// Inherit the prototype from human

Developer.prototype = Object.create(Human.prototype)

// Add the overrridden constructor property again

Developer.prototype.constructor = Developer

Developer.prototype.describeExpertise = function() {

console.log(`Hello I'm ${this.name} and I'm a ${this.expertise}`)

}This is how it looks like with the class syntax:

class Developer extends Human {

constructor(name, age, gender, expertise) {

super(name, age, gender)

this.expertise = expertise

}

describeExpertise() {

console.log(`Hello I'm ${this.name} and I'm a ${this.expertise}`)

}

}Creating objects from class is exactly similar to what we did in the previous section.

let dev = new Developer("Dev", 33, "male", "iOS Developer")

dev.introduce(). // Hey there! I'm Dev

dev.describeExpertise(). // Hello I'm Dev and I'm a iOS DeveloperApart from the things we saw above JavaScript classes have multiple other features like private fields, mixins, getters etc. but those would be out of scope of this article. I would recommend you to check out the MDN docs for classes if you're interested in learning more about them.

Conclusion

To summarize again, in this article we learned what prototypes are and what are they used for, how you can create objects with a custom prototype with constructor functions, what is prototype chaining and how you can achieve prototypal inheritance with it, and finally, how do all these concepts apply to JavaScript classes.

If you made it till here, I hope you learned something new about JavaScript and understand how JavaScript classes work under the hood.

P.S. - The visualizations I created for this article were made with Excalidraw and were inspired by the mental models from Dan Abramov and Maggie Appleton’s Just JavaScript course.