The popularity of React as a UI building library has only been growing and rather accelerating over the past few years. At the time of writing this article, it has 14 million+ weekly npm downloads, which I know isn’t a correct measure for the popularity of a library, but the React Devtools chrome extension alone also has more than 3 million weekly active users. However, the rendering patterns in React have almost been the same until React 18.

So in this article, we’ll be looking at React's current rendering patterns, their problems, and how the new patterns introduced with React 18 aim to fix those problems.

Web vitals terminology

Before we dive into the rendering patterns, let’s look at some web vital terminology that we’ll be using throughout this post:

- Time To First Byte (TTFB) - The time it takes for the client to receive the first byte of content.

- First Paint (FP) - The time when the first pixel gets visible to the user.

- First Contentful Paint (FCP) - The time it takes for the first piece of content to be visible.

- Largest Contentful Paint (LCP) - The time it takes for the main content of the page to be loaded.

- Time To Interactive (TTI) -The time at which the page becomes interactive and reliably responds to user events.

The current rendering patterns

Right now, the most common patterns we use in React are Client-side rendering and Server Side rendering and some advanced forms of server rendering offered by frameworks like Next.js, Static Site Generation, and Incremental Static Regeneration. We’ll look into each of those and dive into the newer patterns introduced with React 18 and available in the future.

Client-Side Rendering (CSR)

Client-side rendering, mostly with create-react-app or other similar starters, was the default way for building React apps for some time before meta-frameworks like Next.js and Remix came along.

With CSR, the server only provides barebones HTML for every page containing the necessary script and link tags. Once the relevant JavaScript is downloaded to the browser. React renders the tree and generates all the DOM nodes. All the logic for routing and data fetching is handled by the client-side JavaScript as well.

To see how it works, let’s consider that we are rendering the below app:

// App.jsx

<Layout>

<Navbar />

<Sidebar />

<RightPane>

<Post />

<Comments />

</RightPane>

</Layout>This is what the render cycle of the above app will look like:

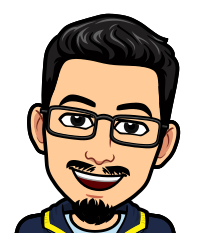

And hence this is the network graph:

So CSR apps have a fast time to first byte because they rely on mostly static assets. However, users must stare at a blank screen until the relevant JavaScript is downloaded. Even after that, most real-world apps would need to fetch data from an API to display relevant data to the users, which leads to a very slow LCP.

Advantages of CSR

- Since the Client-side rendering architecture comprises static files, it can be very easily served via a CDN.

- All the rendering is done on the client hence CSR allows us to have navigations without full page refreshes, providing a good UX.

- The time to the first byte is fast hence the browser can immediately start loading the fonts, CSS, and JavaScript.

Problems with CSR:

- Since all the content is rendered on the client, performance takes a big hit because the users first need to download and process it to see the content on the page.

- Client-side rendering applications usually fetch the data they need on the component mount, leading to a bad user experience since they would be greeted with a bunch of loaders on the initial page load. Also, this can get worse if child components have data fetching requirements, but they are not rendered until their parents have fetched all the data, which can lead to a cascade of loaders and a bad network waterfall.

- Lastly, SEO is a problem with client-side rendering applications because web crawlers can easily read the server-rendered HTML, but they might not wait to download all the JavaScript bundles, execute them and wait for the client-side data fetching waterfalls to finish, which can lead to improper indexing.

Server-side rendering

The way that server-side rendering works in React right now is:

- We fetch relevant data and run the client-side JavaScript on the server for the page via

renderToString, which gives us all the HTML necessary for displaying a page. - This HTML is then served to the client, leading to a fast First Contentful Paint.

- But we’re not done yet; we still need to download and execute the client-side JavaScript to connect the JavaScript logic to the server-generated HTML to make the page interactive (this process is what we call “hydration”). If you are further interested in understanding why rehydration is necessary and how it works, check out The Perils of Rehydration article by Josh.

To better understand how it works, let’s look at the lifecycle of the same app that we saw in the previous section with SSR:

// App.jsx

<Layout>

<Navbar />

<Sidebar />

<RightPane>

<Post />

<Comments />

</RightPane>

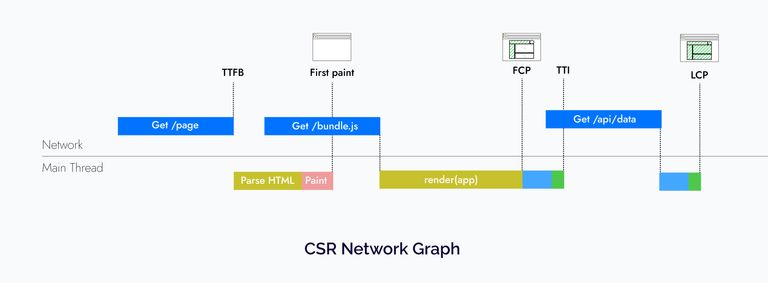

</Layout>And hence this leads to the following network graph:

So with SSR, we get a good FCP and LCP, but the TTFB suffers because we have to fetch data on the server and then convert it to HTML string.

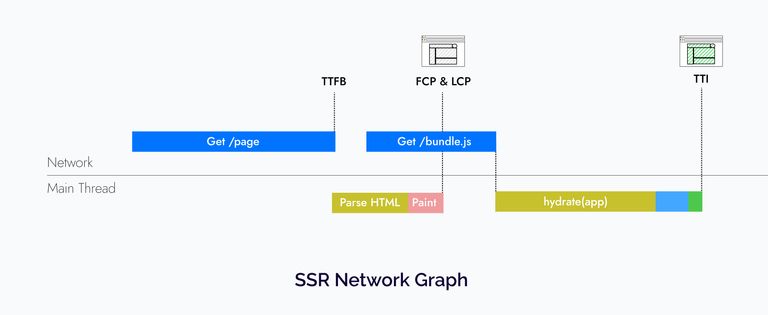

Now you might ask where Next.js’ SSG/ISR fits here. They also have to go through the same process we saw above. The only difference is that they don’t suffer from a slow Time To First byte because the HTML is either generated at build time or is generated and cached incrementally as requests come in.

But SSG/ISR is not a silver bullet; in my experience, they work best for public pages but for pages that change based on the user’s logged-in status or some other cookies stored on the browser, you would have to use SSR.

Advantages of SSR

- Unlike CSR, SEO is much better since all the HTML is pre-generated from the server and web crawlers have no problem crawling through that.

- The FCP and LCP are pretty fast. Hence the user has something to see instead of looking at a blank screen like in the case of CSR apps.

Problems with SSR

Since we are rendering the page on the server first with every request and have to wait for the data requirements for the page, it can lead to a slow TTFB, which can keep the users waiting to look at the browser spinner. This can happen for multiple reasons, including unoptimized server code or many simultaneous server requests.

Although would also like to add that frameworks like Next.js somewhat solve this problem by allowing you to generate pages ahead of time and caching them on the server with techniques like SSG (Static site generation) and ISR (Incremental static site generation).

Lastly, even though the initial load is fast, the users still have to pay to download all the JavaScript for the page and process it so that the page can be rehydrated and become interactive.

The new rendering patterns

In the previous section, we saw that what are the current rendering patterns in React and what are the problems with them. To summarize:

- In CSR apps, the users must download all the necessary JavaScript and execute it to view/interact with the page.

- With SSR, we solve some of these problems by generating the HTML on the server. Yet it is not optimal since first we have to wait on the server to fetch all data and generate the HTML. Then the client has to download the JavaScript for the whole page. Lastly, since hydration is a single pass in React, we have to execute the JavaScript to connect the server-generated HTML and the JavaScript logic so that the page can be interactive. So the primary issue is we have to wait for each step to finish before we can start with the next one.

The React team is working on some new patterns that aim to solve these problems.

Streaming SSR

One cool thing about browsers is that they can receive HTML via HTTP streams. Streaming allows the web server to send data to a client over a single HTTP connection that can remain open indefinitely. So you can load data on the browsers over a network in multiple chunks, which are loaded out of order parallel to rendering.

Streaming before React 18

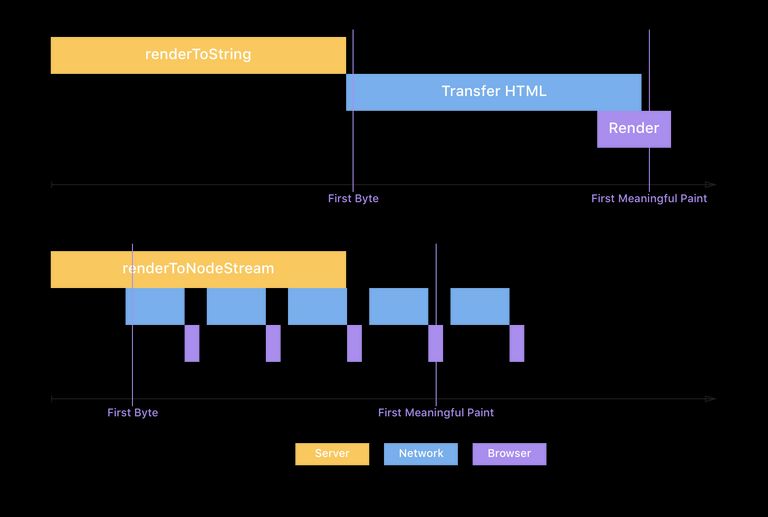

Streaming rendering isn’t something brand new in React 18. In fact, it has existed since React 16. React 16 had a method called renderToNodeStream which, unlike renderToString, rendered the frontend as an HTTP stream to the browser.

This allowed you to send down HTML in chunks parallel to rendering it, enabling a faster time to first byte and largest contentful paint for your users since the initial markup arrives in the browser sooner.

Max Stoiber illustrated the difference nicely in his article about how they used it at Spectrum.

Streaming SSR with React 18

React 18 deprecates the renderToNodeStream API in favor of a newer API called renderToPipeableStream, which unlocks some new features with Suspense that allow you to break down your app into smaller independent units that can go through the steps that we saw with SSR independently. This is possible because of two major features added with Suspense:

- Streaming HTML on the server

- Selective hydration on the client

Streaming HTML on the server

As mentioned previously, the SSR before React 18 was an all or nothing approach; first, you needed to fetch any data requirements that the page had, generate the HTML, and then send it to the client. This is no longer the case, thanks to HTTP streaming.

The way it will work with React 18 is that you can wrap the components that might take a longer time to load and are not immediately required on screen in Suspense. Again to understand how it works, let’s assume that the Comments API is slow, so we wrap the Comments component in Suspense.

<Layout>

<NavBar />

<Sidebar />

<RightPane>

<Post />

<Suspense fallback={<Spinner />}>

<Comments />

</Suspense>

</RightPane>

</Layout>This way, comments are not there in the initial HTML, and the user gets the fallback spinner in its place initially:

<main>

<nav>

<!--NavBar -->

<a href="/">Home</a>

</nav>

<aside>

<!-- Sidebar -->

<a href="/profile">Profile</a>

</aside>

<article>

<!-- Post -->

<p>Hello world</p>

</article>

<section id="comments-spinner">

<!-- Spinner -->

<img width=400 src="spinner.gif" alt="Loading..." />

</section>

</main>Finally, when the data is ready for Comments on the server, React will send minimal HTML to the same stream with an inline script tag to put the HTML in the right place:

<div hidden id="comments">

<!-- Comments -->

<p>First comment</p>

<p>Second comment</p>

</div>

<script>

// This implementation is slightly simplified

document.getElementById('sections-spinner').replaceChildren(

document.getElementById('comments')

);

</script>Hence this solves the first problem since we now don’t have to wait for all the data to be fetched on the server and the browser can start rendering the rest of the app, even if some parts are not ready.

Selective hydration

Even though the HTML got streamed, the page won’t be interactive unless the whole JavaScript for the page is downloaded. That’s where selective hydration comes in.

One way to avoid large bundles on a page during client-side rendering was code-splitting via React.lazy. It specifies that a particular piece of your app doesn’t need to load synchronously, and your bundler would have split it off into a separate script tag.

The limitation with React.lazy was that it doesn’t work with server-side rendering, but now with React 18, <Suspense> apart from allowing you to stream the HTML, it also lets you unblock hydration for the rest of the app.

So now, React.lazy works out of the box on the server. When you wrap your lazy component in <Suspense>, you not only tell React that you want it to be streamed but also allow the rest of hydrated even if the component wrapped in <Suspense> is still being streamed. This also solves the second problem that we saw in traditional server-side rendering. You no longer have to wait for all the JavaScript to be downloaded before you start hydrating.

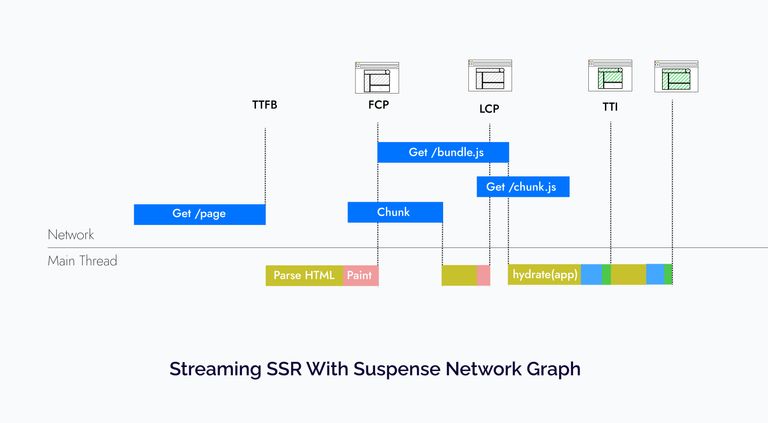

Again, let’s look at the lifecycle of the app with Comments wrapped in Suspense, and using the new Suspense Architecture

<Layout>

<NavBar />

<Sidebar />

<RightPane>

<Post />

<Suspense fallback={<Spinner />}>

<Comments />

</Suspense>

</RightPane>

</Layout>This leads to a network graph that looks something like this:

Again this is a very contrived example, but what it is trying to demonstrate is that with Suspense a lot of stuff that was happening serially now happens in parallel.

Which helps us in not only getting a faster time to first byte since the HTML was streamed but also, the users don’t have to wait for all the JavaScript to be downloaded to be able to start interacting with the app. Other benefits about streaming rendering that I could not include in this network graph is that it also helps load other assets (CSS, JavaScript, fonts, etc.) as soon as the page starts streaming, helping parallelizing even more requests, as Ryan mentioned in his talk.

Another cool thing is that if you have multiple components wrapped in Suspense and haven’t been hydrated on the client yet, but the user starts interacting with one of them, React will prioritize hydrating that component first. You can check this out and all the things discussed above in more detail in the New Suspense Architecture discussion.

Server components (Alpha)

In the last section, we saw how we could improve the server-side rendering performance by breaking our app into smaller units and streaming and hydrating them separately. But what if there was a way where you didn’t need to hydrate parts of your application at all?

Well, this is where the new Server Components RFC comes in which is meant to compliment server-side rendering, allowing you to have components that only render on the server and have no interactivity.

To give a brief overview, the way they work is that you can create non-interactive server components with .server.js/jsx/ts/tsx extensions, and they can then seamlessly integrate and pass props to client components (with .client.js/jsx/ts/tsx extensions) which can handle the interactive parts of the page. Here is a more detailed list of the features that they offer:

Zero client-side bundle: Server components are only rendered on the server and don’t need to be hydrated. They allow us to render static content on the server while incurring zero effect on the client-side bundle size. This can be particularly useful if you’re using a heavy library and has no interactivity, and it can be completely rendered on the server with no effect on the client-side bundle. A great example of this would be the Notes preview from the RFC:

// NoteWithMarkdown.js

// NOTE: *before* Server Components

import marked from 'marked'; // 35.9K (11.2K gzipped)

import sanitizeHtml from 'sanitize-html'; // 206K (63.3K gzipped)

function NoteWithMarkdown({text}) {

const html = sanitizeHtml(marked(text));

return (/* render */);

}// NoteWithMarkdown.server.js - Server Component === zero bundle size

import marked from 'marked'; // zero bundle size

import sanitizeHtml from 'sanitize-html'; // zero bundle size

function NoteWithMarkdown({text}) {

// same as before

}Server components don’t have interactivity but can compose with client components for it: Since they only render on the server, they are just React component that takes in props and renders a view. Hence they can’t have stuff like state, effects, and event handlers like we have with regular client components.

Although they can import client components that can have interactivity and be hydrated when rendered on the client, as we saw with normal SSR. Client components similar to their server counterparts are defined with

.client.jsxor.client.tsxsuffix.This composability allows the developers to save significant bundle size on pages, like detail pages with mostly static content with few interactive elements. For example:

// Post.server.js

import { parseISO, format } from 'date-fns';

import marked from 'marked';

import sanitizeHtml from 'sanitize-html';

import Comments from '../Comments.server.jsx'

// Importing a client component

import AddComment from '../AddComment.client.jsx';

function Post({ content, created_at, title, slug }) {

const html = sanitizeHtml(marked(content));

const formattedDate = format(parseISO(created_at), 'dd/MM/yyyy')

return (

<main>

<h1>{title}</h1>

<span>Posted on {formattedDate}</span>

{content}

<AddComment slug={slug} />

<Comments slug={slug} />

</main>

)

}// AddComment.client.js

function AddComment({ hasUpvoted, postSlug }) {

const [comment, setComment] = useState('');

function handleCommentChange(event) {

setComment(event.target.value);

}

function handleSubmit() {

// ..post the comment

}

return (

<form onSubmit={handleSubmit}>

<textarea name="comment" onChange={handleCommentChange} value={comment}/>

<button type="submit">

Comment

</button>

</form>

)

}The above snippets are just a contrived example of how server components compose with client components. Let’s break it down:

- We have the

Postserver component, which has mostly static data, including the post title, content, and the date it was published. - Since server components can’t have any interactivity, we have imported a client component called

AddComment, which enables the user to add a comment.

The thing I love the most here is that all the date and markdown parsing libraries we imported in the server component are never downloaded on the client. The only JavaScript we download on the client is for the

AddCommentcomponent.- We have the

Server components can access the backend directly: Since they are only rendered on the server, you can use them to access databases, and other backend-only data sources, directly from your components, like this:

// Post.server.js

import { parseISO, format } from 'date-fns';

import marked from 'marked';

import sanitizeHtml from 'sanitize-html';

import db from 'db.server';

// Importing a client component

import Upvote from '../Upvote.client.js';

function Post({ slug }) {

// Reading the data directly from the database

const { content, created_at, title } = db.posts.get(slug);

const html = sanitizeHtml(marked(content));

const formattedDate = format(parseISO(created_at), 'dd/MM/yyyy');

return (

<main>

<h1>{title}</h1>

<span>Posted on {formattedDate}</span>

{content}

<AddComment slug={slug} />

<Comments slug={slug} />

</main>

);

}Now you might argue that you could do this in traditional server-side rendering. For instance, Next.js allows you to access the server data directly in

getServerSidePropsandgetStaticProps. And you won’t be wrong, but the difference is traditional SSR is an all-or-nothing approach and can only be done on a top-level page, but server components allow you to do that on a per-component basis.Automatic code-splitting: Code-splitting is a concept that allows you to break your application into smaller chunks, sending less code to the client. The most common way you code split your app is per route. That’s also how frameworks like Next.js split the bundles for you by default.

Apart from automatic code-splitting, React also allows you to lazily load different modules at runtime with

React.lazyAPI. Here is again a great example from the RFC on where this might be particularly useful:// PhotoRenderer.js

// NOTE: *before* Server Components

import React from 'react';

// one of these will start loading *when rendered on the client*:

const OldPhotoRenderer = React.lazy(() => import('./OldPhotoRenderer.js'));

const NewPhotoRenderer = React.lazy(() => import('./NewPhotoRenderer.js'));

function Photo(props) {

// Switch on feature flags, logged in/out, type of content, etc:

if (FeatureFlags.useNewPhotoRenderer) {

return <NewPhotoRenderer {...props} />;

} else {

return <OldPhotoRenderer {...props} />;

}

}This technique does improve performance by dynamically importing only the component you need at runtime, but it does have some of its own caveats. For instance, this approach delays when the application can start loading the code, negating the benefit of loading less code in the first place.

As we saw earlier on how client components compose with the server components, they solve this problem by treating all client component imports as potential code split points and allowing developers to choose what they want to render much earlier on the server, which allows the client to download it earlier. Here is again the same

PhotoRendererexample from the RFC with server components:// PhotoRenderer.server.js - Server Component

import React from 'react';

// one of these will start loading *once rendered and streamed to the client*:

import OldPhotoRenderer from './OldPhotoRenderer.client.js';

import NewPhotoRenderer from './NewPhotoRenderer.client.js';

function Photo(props) {

// Switch on feature flags, logged in/out, type of content, etc:

if (FeatureFlags.useNewPhotoRenderer) {

return <NewPhotoRenderer {...props} />;

} else {

return <OldPhotoRenderer {...props} />;

}

}Server components can be reloaded while preserving client state: We can refetch the server tree anytime from the client to get the updated state from the server without blowing up the local client state, focus, and even ongoing animations.

This is possible because the description of the UI received is data and not plain HTML, which allows React to merge data into existing components allowing the client state to not be blown away.

Although based on the RFC as of now, the entire subtree needs to be prefetched, given some starting server components and props.

Server components integrate with Suspense out of the box: Server components are can be streamed progressively with

<Suspense>as we saw in the previous section, which allows you to craft intentional loading states and quickly show important content while waiting for the remainder of the page to load.

Now let’s check out how the app we have been looking at throughout this article would look with React Server Components. This time the Sidebar and the Post are server components, and the Navbar and the Comments section are client components. We have also wrapped the Post in Suspense as well.

<Layout>

<NavBar />

<SidebarServerComponent />

<RightPane>

<Suspense fallback={<Spinner />}>

<PostServerComponent />

</Suspense>

<Suspense fallback={<Spinner />}>

<Comments />

</Suspense>

</RightPane>

</Layout>The network graph for this would be very similar to the streaming rendering with Suspense one with way less JavaScript.

So server components are even a further step to fix the problems that we started with, and they not only help us download way less JavaScript but also significantly improve the developer experience.

The React team also mentioned in the RFC FAQs that they ran an experiment with a small number of users on a single page at Facebook and they have with encouraging results with ~30% product code size reduction.

When can you start using these features?

Update

React Server Components are stable now and can be used in production with the Next.js app directory with v13.4 and later. You can read the Next.js docs for more info and also checkout my new blog where I compare building a Twitter Clone with Next.js and React Server Components and Remix.

Original answer

Well, Not yet.

You can try some demos that I have linked in the next section, but at the time of writing this article, Server Components are still in alpha, and Suspense for data fetching, which is needed for the Streaming SSR with new Suspense architecture, still isn’t official yet and will be released with a minor update of React 18.

And the React team also mentioned that all this stuff would be pretty complex so, they expect the initial adoption would be through frameworks. So you should keep an eye out for the Next.js Layouts RFC, which they are saying will be the biggest update to Next.js since its inception, and it will be built on top of the new React 18 features we discussed in this article.

Demos

You can check out the demos by the React team and the Next.js teams here:

- Streaming SSR with the new Suspense Architecture demo

- Server Components Demo

- Next.js Server Components Demo

References

Here are some of the references I used while writing this article:

- Most of the content for this article was inspired by the New Suspense Architecture Discussion and the Server Components RFC and Talk

- Advanced Rendering Patterns: Lydia Hallie

- Rendering on the web